The Urgency of Now

A small group of scientists is unlocking the mysteries of spring Chinook—right as the species nears extinction. Can we still save a fish critical to the Northwest’s future?

Part I, in the First Salmon Last Chance story series.

By Ramona DeNies

An estuary mixes with the Pacific, its channels braided in deep green, dun, and cobalt blue. In a long, glassy tail-out, one pool looks alive—churning and flashing silver in the bright May sun, drawing in curious cormorants, gulls, and a few still-distant seals.

These are spring Chinook, and they seem to be playing: slicing v-wakes, rolling purple-gray backs onto iridescent sides. The salmon move through the water with muscle, strong from years of marine forage. They weave like music, in no apparent hurry to start their final journey.

Perhaps they should. For millennia, spring Chinook returned in staggering numbers to rivers from central California north to the Fraser in British Columbia. Their inscrutable behavior—arriving early in the year and holding in freshwater till fall spawning—is part of a bold and unique survival strategy. Success depends on their ability to climb high in river systems, claiming distant spawning grounds unavailable to later salmon. This gamble takes time and energy, so spring Chinook return from the ocean plump enough to fast for months. To the Indigenous salmon people of the West Coast, this dazzling fish means everything: new life, health, vital sustenance, the annual physical and spiritual renewal of the world.

The inscrutable behavior of spring Chinook—arriving early in the year and holding in freshwater till fall spawning—is part of a bold and unique survival strategy.

But not all humans living here have shown similar respect. More than 150 years after western contact, the pristine Chinook strongholds of the past are unrecognizable: dammed, ditched, and straightened, overfished and scarred by mining, made volatile and hot by deforestation. To complete their journey, these ancient, hardy travelers—whose ancestors survived ice ages and landslides, predators and floods—must now survive us.

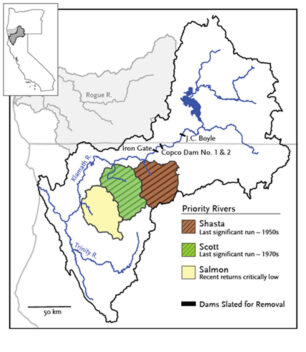

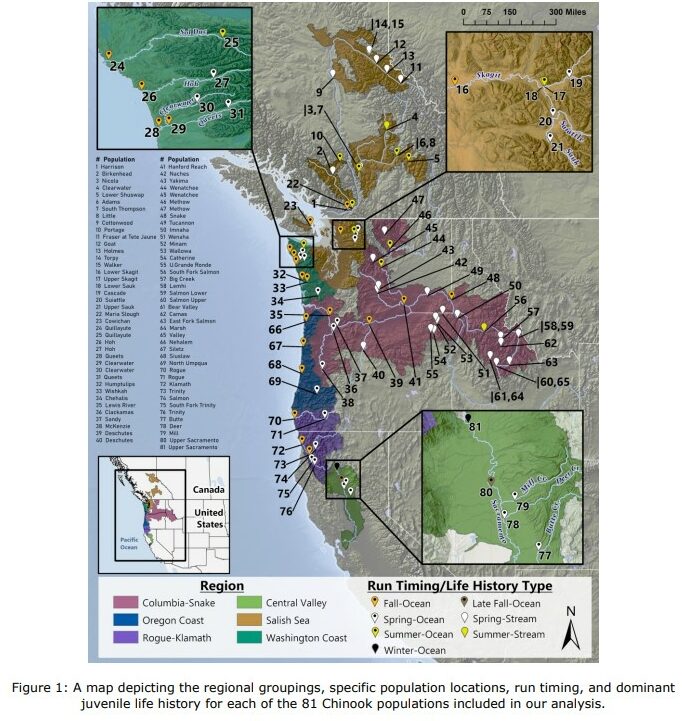

We’re proving an existential threat. In recent decades, scientists and salmon managers have tracked a precipitous decline in spring Chinook runs across their range. In California’s Shasta River, once a salmon stronghold, spring Chinook have been functionally extinct for decades. In the upper Columbia, they’re driving a heated debate over hydropower dam removal. And in the Fraser, dwindling spring runs are linked to the heartbreaking starvation of coastal Southern Resident orcas.

In these dark days for spring Chinook, there is fresh hope: on the Klamath River, where springers still run, four massive dams are slated for removal. Here, Tribes and scientists are fighting to make sure we’re not too late. The alternative is shattering: will we be the last humans to live with the first salmon?

9 a.m. on a storm-threatening morning in late July. Amy Fingerle stands knee-deep in the upper Salmon River, a tributary of northern California’s remote Klamath River. She’s heard people say that spring Chinook here once outnumbered all other salmon, but that’s hard to prove without official records. None really existed until at least the 1960s—and none good, she stresses, until the 1990s, when the Salmon River Restoration Council began coordinating its annual fish dives.

Fingerle would know; for several years she helped run the dives. Now a doctoral student at UC-Berkeley, she’s returned for the 2020 counts, this time as an expert volunteer. Spring Chinook are her passion, and she feels personally invested in their success.

Now, snorkeled and snug in her wetsuit, Fingerle wades to one side of the river and waves at her survey partner across the main channel. Today the pair will walk, swim, and stumble their way five miles down this canyon-walled river stretch, surveying for returning spring Chinook.

It’s the final day of the three-day dive, and Fingerle is excited; she worked this stretch last year and still remembers exactly where she saw each of the 11 fish she counted. Not many, she admits, but Fingerle reminds herself that if she sees even one springer—as fish folk call them—then maybe her fellow surveyors upriver and down are spotting more.

Two miles without sightings, and she remains stoic. Then hopeful: the pair is approaching a stretch of deep pools and the cool, aerated confluence of Knownothing Creek—all excellent habitat for spring Chinook riding out the summer heat.

“I saw several here last year,” Fingerle says, recalling that moment. “The best part was that I was with someone new to the survey, and I got to watch her face light up—that’s one of the true joys of doing this work.”

She remembers being a bit chilly in her wetsuit then, but now, as she snorkels slowly by the creek confluence, she realizes she’s far too warm. At these temperatures, fish struggle to breathe; they also burn too quickly through precious energy reserves, and are more vulnerable to disease. If they were here, they’ve fled; one after another, the pools are empty.

At these temperatures, fish struggle to breathe; they also burn too quickly through precious energy reserves, and are more vulnerable to disease.

Tamping down a growing unease, Fingerle presses on through the last mile. Water turbidity increases, making it hard to see, but now, more than ever, Fingerle and her partner are determined not to miss a single flash of bright silver. Their concentration is acute, even grim. And then, with the midafternoon sun riding high above them, a distant bridge becomes visible on the horizon—the endpoint of their survey stretch.

“That’s when I started feeling panicky,” Fingerle says later. “We’d seen mergansers, bald eagles, even a steelhead. I told my partner to go ahead; if there were any springers to be observed, this would be the place, and I wanted him to have that experience.”

None. Defeated, the pair exited the river, wrote zeroes on their survey sheet, and reported back to survey headquarters. They were the first team to return.

“I had to hope that the fish had just gone higher in the watershed,” Fingerle says. “I had to hope that if the water was too warm downstream, they’d moved upstream.”

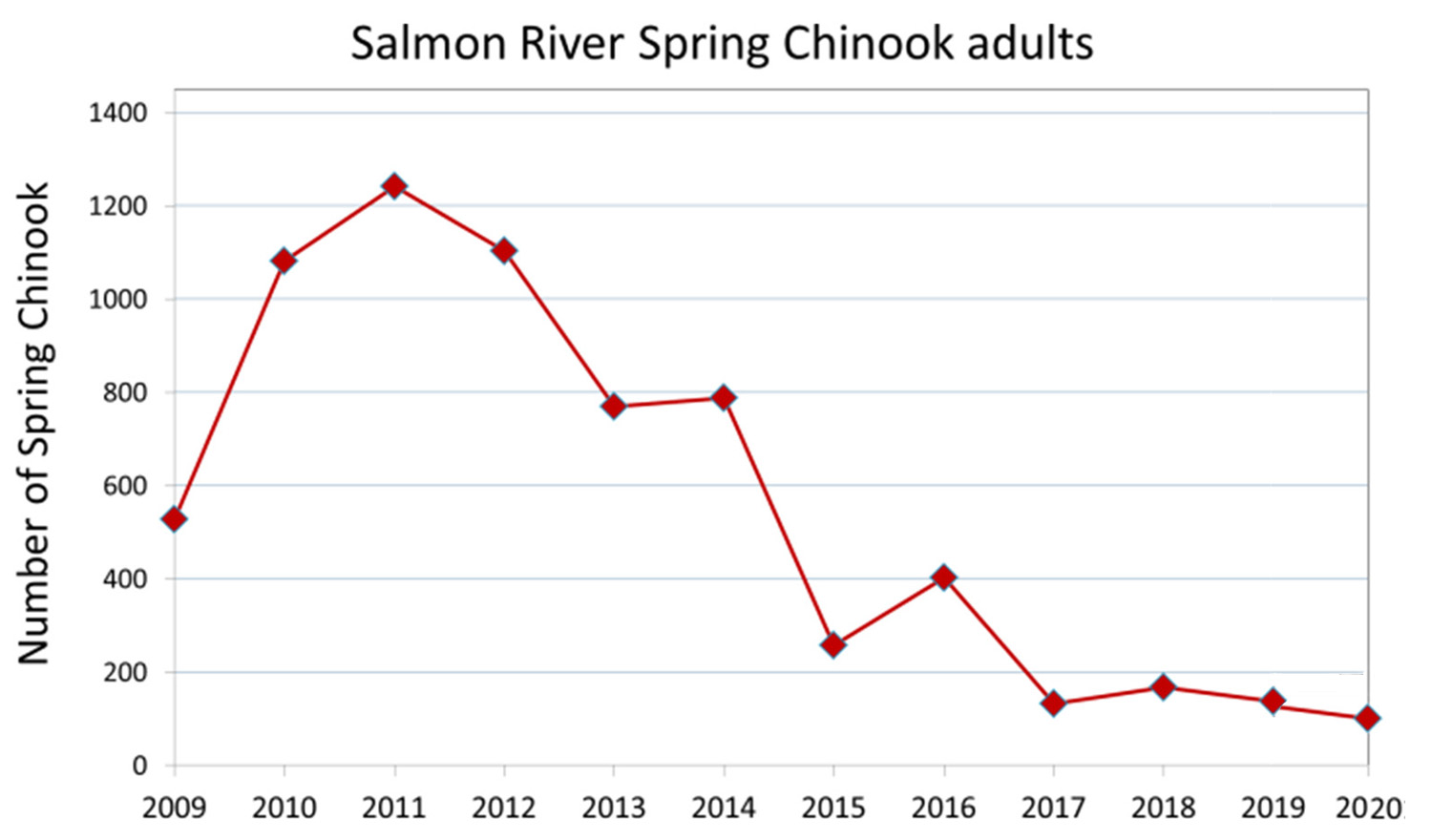

The next day, Fingerle heard the final total count for the 2020 Salmon River spring Chinook dive: just 106 spring Chinook across 83 river miles. The tally marks a staggering population decline in a river that saw more than 1,500 spring Chinook as recently as 2011—a number that itself represents a mere drop in the historical bucket.

At these levels the risk of extinction becomes very real. You can feel it.

For the fourth straight year, the annual dive had tallied fewer than 400 fish. At these levels, says Wild Salmon Center Science Director Dr. Matt Sloat, the risk of extinction becomes very real. You can feel it. Weeks after the dive, Fingerle fell into a deep, confusing depression. It took help from her friend Jason Reed, a Hoopa tribal member of Karuk and Yurok descent, to trace that funk back to her springerless swim.

Just 106 fish—and yet Klamath and Trinity River spring Chinook aren’t listed under the Endangered Species Act, as some runs are in the upper Columbia and California’s Central Valley.

Matt Sloat ponders this reality from his home office in Corvallis, Oregon, between fielding calls from colleagues and “help” from his fish-crazed six-year-old daughter. In his own early years, Wild Salmon Center’s senior fisheries scientist spent summers at a family cabin on the Trinity, fishing from Junction City downstream to Weitchpec. Now, he’s casting for hope that its salmon and steelhead will survive to dodge his grandchildren’s fishing rods.

“The situation on these rivers is dire,” he says. “The annual dive counts seem to be chronicling a species nearing the brink. Yet it’s been hard to get anyone’s attention.”

One problem, he says, is that it’s tricky to compare today’s salmon runs with the past. Oral histories, photos, and personal accounts from the early 20th century imply that 20-pound springers returned to the Klamath and Trinity in huge numbers. But the records to prove it are scarce. So salmon managers and policymakers set baselines from more recent data: runs already vastly dwindled, or even vanished.

“Springers are essentially gone from the Shasta and Scott, where they once numbered in the thousands,” says Dr. Sloat. “In the South Fork of the Trinity, springer returns were close to 10,000 fish in the early 1960s. And this year they counted what, maybe 11 fish? We’ve got to recognize the magnitude of what’s already been lost, or we won’t meet the urgency of this moment.”

Another problem, says Dr. Sloat, is how long it’s taken western science to distinguish springers from larger fall Chinook runs. To the Karuk and Yurok Tribes, who have fished the Klamath for millennia, spring Chinook have always been their own, distinct animal. But federal and regional agencies often lump the two cousins in the same management schemes, muddying both the specifics and seriousness of springers’ decline.

“Because spring Chinook arrive early, they can hopscotch up rivers in hot months,” says Dr. Sloat. “Early return is their only competitive edge over other salmon, who’ve got just one shot to reach their spawning grounds. Springers lose that advantage the minute that fall Chinook can spawn with them—or worse, replace their run wholesale.”

Now, scientific breakthroughs are unlocking the secrets of this amazing fish, and powerful, grassroots efforts are reasserting Indigenous knowledge in how we manage salmon rivers. From the Rogue River to Puget Sound, this new way of thinking is amplifying efforts to reopen and restore the upper river reaches that springers need. On the Klamath, it’s driving a high-stakes campaign to recover spring Chinook while there’s still time. Without spring Chinook, say the campaigners, the long-promised teardown of four dams on the California-Oregon border—the largest dam removal in history—will be a hollow victory.

“The science is finally clear on this: if you lose a spring Chinook run, it’s gone for good,” says Dr Sloat. “We’re running out of time for the Klamath and many other rivers.”

Those 106 Salmon River springers need our help, and fast.

Spring Chinook Series | Part I | Part II | Part III | Part IV