For fans of wild salmon, it’s hard to know what’s the right choice in a restaurant or at a store. Here’s why one famous Seattle chef loves Columbia River trap-caught coho.

Last summer, Seattle restaurateur Renee Erickson yanked Chinook from her menus.

“I didn’t see any good reason to keep serving it,” said the James Beard Award-winning chef, whose empire includes Barnacle, the Walrus and the Carpenter, and the Whale Wins. “There’s a chunk of me, like many people, that wonders whether we should be eating salmon at all.”

Erickson’s decision followed national news coverage of Tahlequah, a Southern Resident orca off the Washington Coast who carried her dead calf—likely starved—for a heartbreaking 17 days.

Erickson isn’t alone in wondering what salmon she could, or should, be serving. As wild salmon runs decline around the North Pacific, the impacts are real for the 137 species (like Southern Resident orcas) that rely on them. For conservation-minded chefs and diners, it can be hard to know which fisheries are sustainable, who to trust, and what to make of ever-shifting marketplace lingo like “wild-caught.” Consumer seafood guides can help. But saying “I’ll have the salmon” can still sometimes feel like a fraught black box of, just, no.

And yet, roughly one year after giving up Chinook, Erickson’s saying yes to coho—boxes of it, caught at an experimental fish trap being tested three hours south of Seattle on the Columbia River.

“It redefined what we can serve people,” says Erickson. “The trap avoids all the noise, the engines, the plastic, the nets.”

Erickson first learned of Columbia River trap-caught coho through the Wild Fish Conservancy, a nonprofit that, with the Washington Department of Fish & Wildlife, is running the first fish trap on the Columbia River in 85 years. (Wild Salmon Center is a supporting partner of the project.)

Fish traps, also called pound nets, were once widespread along the West Coast. According to WFC biologist Adrian Tuohy, the traps’ appeal (and ultimate downfall) was their efficiency at catching fish. During the Great Depression, wildly successful fish traps—often owned by corporate cannery operators—became targets for competing gillnetters and sport fishermen. Traps were outlawed in Washington in 1934; Oregon followed in 1948. At statehood in 1959, Alaska wrote a ban into its own constitution.

Fast forward to 2016, when WFC brokered a deal with the state of Washington to begin testing local fisherman Blair Peterson’s prototype trap as a tool for saving wild salmon. Because of the trap’s passive engineering—it’s essentially a watery, non-threatening corral—Peterson and WFC argued it could solve a key need for the Columbia River’s fisheries: finding a way to catch abundant hatchery fish without killing the river’s threatened wild salmon and steelhead stocks in the process.

This summer, data published by the Wild Fish Conservancy proved the experiment successful, with studies showing the trap can operate with near zero mortality for wild salmon and other bycatch. It’s also orca-safe by default, located well above the river mouth. Says Tuohy, “the orcas already had their chance” to catch these fish in the ocean. The next step is to convince Washington State to lift its ban on traps, and then, hopefully, convert others.

It redefined what we can serve people,” says Erickson. “The trap avoids all the noise, the engines, the plastic, the nets.”

For chefs like Erickson, there’s admittedly another incentive: this fish is delicious. Tuohy says his team can move a coho from water to net to ice locker, fully bled, in nine seconds or less. That means minimal handling and stress: no bruising, scale loss, or lactic buildup in its flesh. And because it’s just one river mile to the seafood processor, Erickson can get her coho within three hours, still in full rigor, as fresh as it gets.

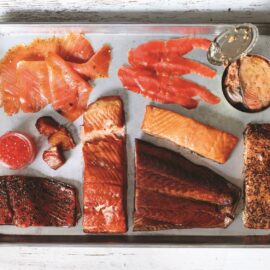

“Fish out of a trap is remarkable; it’s untouched, pristine,” says Erickson. “We roast it in butter, cure it. There’s very little you should do to it when it’s so fresh and perfect.”

WHAT IT IS: Columbia River Trap-Caught Coho is the market name for hatchery coho harvested in an experimental fish trap on the lower Columbia River.

WHY IT’S KEY: The trap—the first in Washington state since a 1934 ban—is being tested as a selective fishing gear type, one that can harvest hatchery salmon while allowing safe passage for wild salmon and other bycatch.

WHERE TO FIND: If Washington legalizes fish traps, fresh Columbia River Trap-Caught Coho might make it to local fish markets as soon as summer 2020; till then, a few lucky buyers are snapping up the fish trap’s limited harvest from C&H Classic Smoked Fish.